search

date/time

| Yorkshire Times A Voice of the Free Press |

Paul Spalding-Mulcock

Features Writer

@MulcockPaul

6:18 PM 15th April 2021

arts

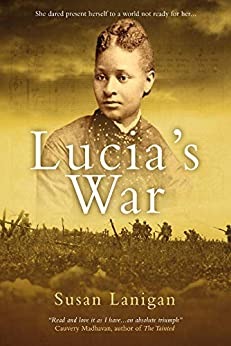

'Zugzwang...no Move Without Loss': Lucia's War By Susan Lanigan

Susan Lanigan is an author who practices the ‘art’ Welty extolls. Author of White Feathers, a historical World War One novel shortlisted for the ‘Romantic Novel of the Year Award’ in 2015, she has been thrice shortlisted for the ‘Hennessy New Irish Writing Award’ and is an ‘Irish Writer’s Centre Novel Fair’ Winner. Her second novel, Lucia’s War published in 2020 is the work of a truly accomplished writer and though her first literary outings were impressive feats of authorial éclat, her latest offering is a scintillating, emotive gem and a marvellous testament to the constructive potency of the historical fiction genre.

Lanigan both observes the literary conventions of her chosen form, whilst simultaneously disregarding the banal impositions foisted upon those writing within this genre. The effect is the penning of a novel of dazzling originality and compelling verisimilitude.

Admirers of Andrea Levy will be instantly at home within the pages of Lucia’s War, for as with Levy’s novels, Small Island and The Long Song, Lanigan also explores the experiences of those belonging to the Jamaican diaspora living amongst an indigenous and innately racist population. Both authors examine how such unmoored characters negotiate racial, cultural and societal bias and struggle to survive the iniquities of inequality and abuse.

Cauvery Madhavan’s stunningly frank, yet tender novel, The Tainted tackled the legacy of colonisation and the ineluctable trials and tribulations endured by those born outside its prevailing social mores. Again, fans of Madhavan will find in Lanigan another voice of similar artistic virtuosity speaking truths to both their hearts and minds. Though Lanigan may share a thematic congruity with other historical fiction writers, her latest novel is breathtakingly original in terms of the creative method by which she responds to humanistic travesties, and the appalling consequences faced by those weathering the storms of capricious fate, cruelly exacerbated by man’s unconscionable inhumanity to man.

As with Madhavan’s triumph, Lanigan may hold the reader’s feet to the fire, however we leave her novel not scorched by the flames of unpalatable truths, but cathartically rejuvenated and warmed from within by her novel’s uplifting celebration of courage, compassion and inexorable faith in meliorism. Entertained, enlightened and enraptured, I finished this book with moist eyes and the deep satisfaction of having being drawn through its pages by an author of real legerdemain and artistic panache.

So, to the plot. London, 1950 where we encounter Lucia Percival, a Jamaican-born opera singer about to perform at the Royal Albert Hall. However, the dark secrets of her past during the First world War have overtaken our divinely gifted diva and enervated her redoubtable moxie to the point of personal collapse. We travel back to London in 1917 witnessing Lucia’s journey from young Jamaican exile, harbouring aspirations to become a professional musician, and her meeting with Lilian Shandlin, an old woman irreparably damaged by the brutal consequences of war and the malversations of those orchestrating it.

The two women are conjoined by mutual grief and a longing for resolution on the part of one and vengeance on the part of the other. We encompass the dank waters of the Clyde and the danker depths of Glasgow’s unapologetic racist denizens. The battlefields of France weave their way into our multi-stranded story, finally returning us to the wartime grief saturating 1950 London. This is the story, told in the first person point of view of a black woman ‘more sinned against than sinning’, set against the backdrop of world war as she tenaciously fights for personal happiness and professional success. Her antagonists are blatant racism, betrayal, libidinous moral turpitude, pusillanimous lovers and her own akrasia, augmented by the unbreakable bonds of motherhood and the callous tentacles of intractable guilt and grief.

The structure of the novel inventively eschews the perils of the narrative becoming a confusing, melodramatic megillah. Lanigan’s ace in the hole is to have cast her story in operatic form. We have a prologue acting as frame story. Part One of the ‘opera’ provides both the novel’s conflict and the biographical background of our much maligned protagonist serving as de facto ‘Act One’ of a bourgeois tragic operetta. Part Two takes us forward in time, enabling a confessional retrospective first person account of the preceding years and their horrific events, now relayed through the prism of our battle-scarred protagonist recalling and interpreting her past experiences and injudicious choices.

Susan Lanigan

Clever use of the epistolic form garners verisimilitude, lending the novel far more than the semblance of autobiographical fact. Notable black musical luminaries feature in the story, though their names have been altered, again conferring credibility and cultural texture upon the novel’s events. Most significantly, Lanigan has melded the argot of the operatic canon into her delightfully modulated prose. Her figurative language draws upon musically inspired similes and metaphors, constantly enveloping the reader with the sense that Lucia is ‘an opera singer, and drama my natural home’.

Prose descriptions are imbued with a musical lexicon, the lyrical rhythm of her sentences wrapping us up in the operatic sub-texture of the novel: ‘It had begun to rain, in that dismal wintry fashion, and the wind started a low G with eerie harmonic overtones…’. Lucia’s musicality is the very quintessence of her soul and the fissile line creating the fissure in her mind and lived world. Musical references permeate the pages like notes the bars of a concerto score. ‘The two parts of me – musician versus mother, public versus private…no way of reconciling the two’ as she collides with a prejudiced zeitgeist recalcitrant in ‘tooth and claw’, to her the achievement of her private and personal hopes. The musical world she so craved to join had once turned her away from the Royal Academy because ‘they did not need a cleaner’.

Lucia slips into the idiolect of her oppressed ancestors, these colourful colloquialisms acting as atonal sharp notes counterpointing the flat register of the stilted conventional English vernacular of the period. This Schoenberg-like device simultaneously expresses Lucia’s repressed, authentic persona, whilst also jarringly reminding us that she is an outsider and ‘…there is nothing lonelier than living amongst the English when you are not of their race’. We are never able to forget that Lucia is L’Autre personified, however polished her conversation, erudition and conspicuous intelligence.

Lanigan sprinkles her magic upon the novel’s themes, embedding them with dextrous elan. Following Beckett’s advice to ensure that the artist remains invisible in their art, themes themselves are revealed by dint of creative deliquescence operating upon the printed words. Lanigan transforms her themes into a wide river which flows through Lucia’s turbulent life and as such their promulgation is profound yet felt en masse rather than tediously expostulated and thereby shattering the novel’s realism.

We orbit motherhood and its capacity to engender profound sorrow and grief. Thematic couplets counterpoint each other, syncopated ideological rhythms put in train by dint of the dynamic exchange between antithetical tropes. Revenge illumes forgiveness, fidelity throws betrayal into unflattering light, art and culture sit awkwardly against pedestrian intolerance and ignorance. However, the sickness of war poisons society, a moral septicaemia catalysing indignant violence both physical and emotional. Racism and the rank abuse of people ‘tainted’ by their skin tone is the novel’s refrain; love, hate and loss embellishes the melancholic melody. Redemption serves to overwhelm all that has gone before, and the reader is left battered by pathos, and uplifted by the perduring forces of hope, family and acceptance.

Also by Paul Spalding-Mulcock...

Word Of The Week : CorpusThe Gallery, Slaithwaite: ‘Ten’ - A Birthday ExhibitionWord Of The Week : SibilantWord Of The Week : PropinquityWord Of The Week : IdiosyncrasyE.M. Forster’s Howards End has us witness the squalid collateral damage when the prose and poetry of life clash rather than ‘connect’. An illegitimate child conceived in the hopeless wastes of a forbidden, desperate coupling allows Forster to move his reader nearly to tears. For this jaded reviewer, Lanigan did much the same, for the final line of her wondrous novel has no less force than Forster’s gem. Lanigan may not be E. M. Forster, but she is Susan Lanigan and for that we should all be grateful.

Lucia's War is published by Idée Fixe